Joe & Corinna: A Legacy of Art, Egyptology & ARCE

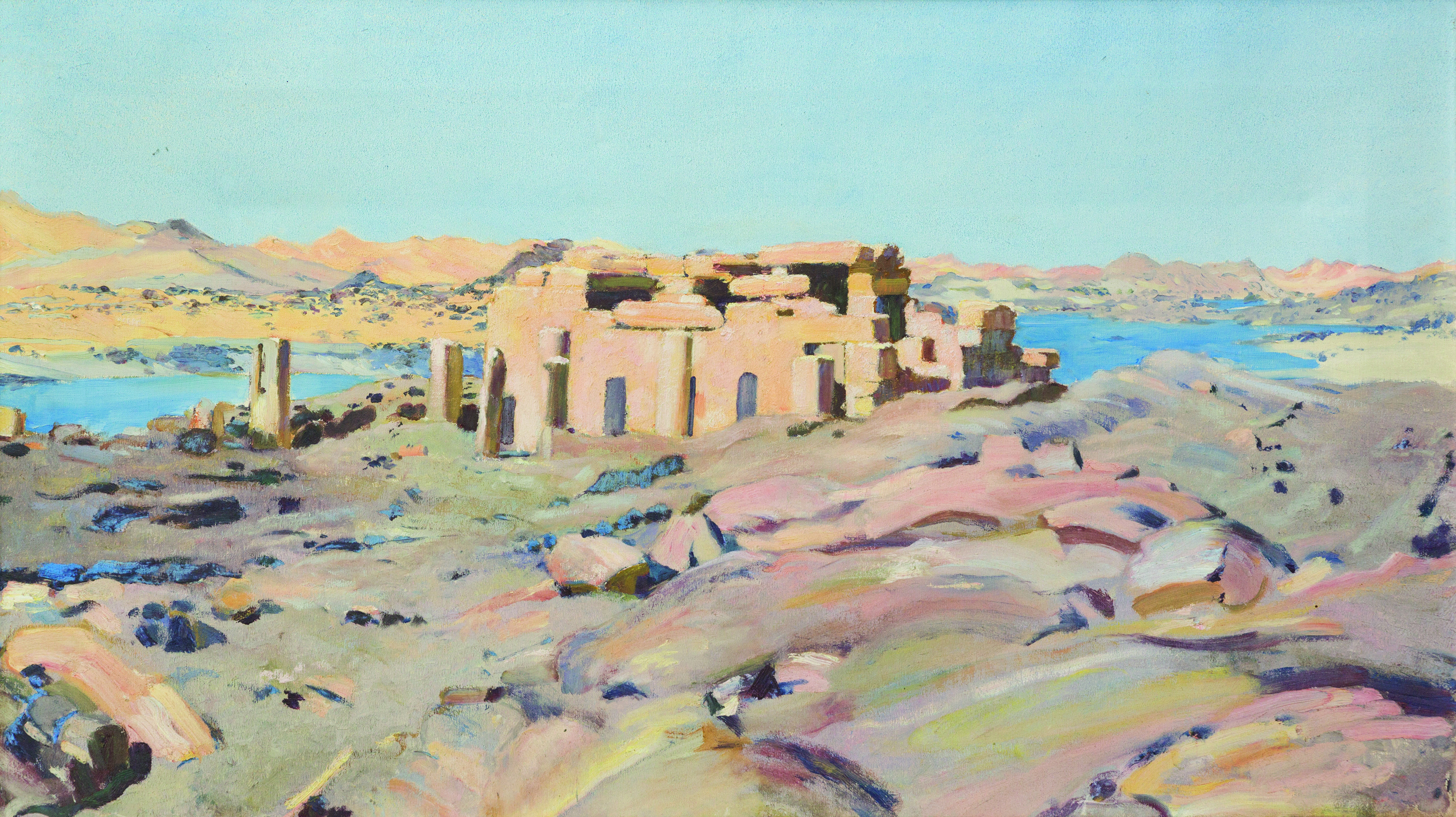

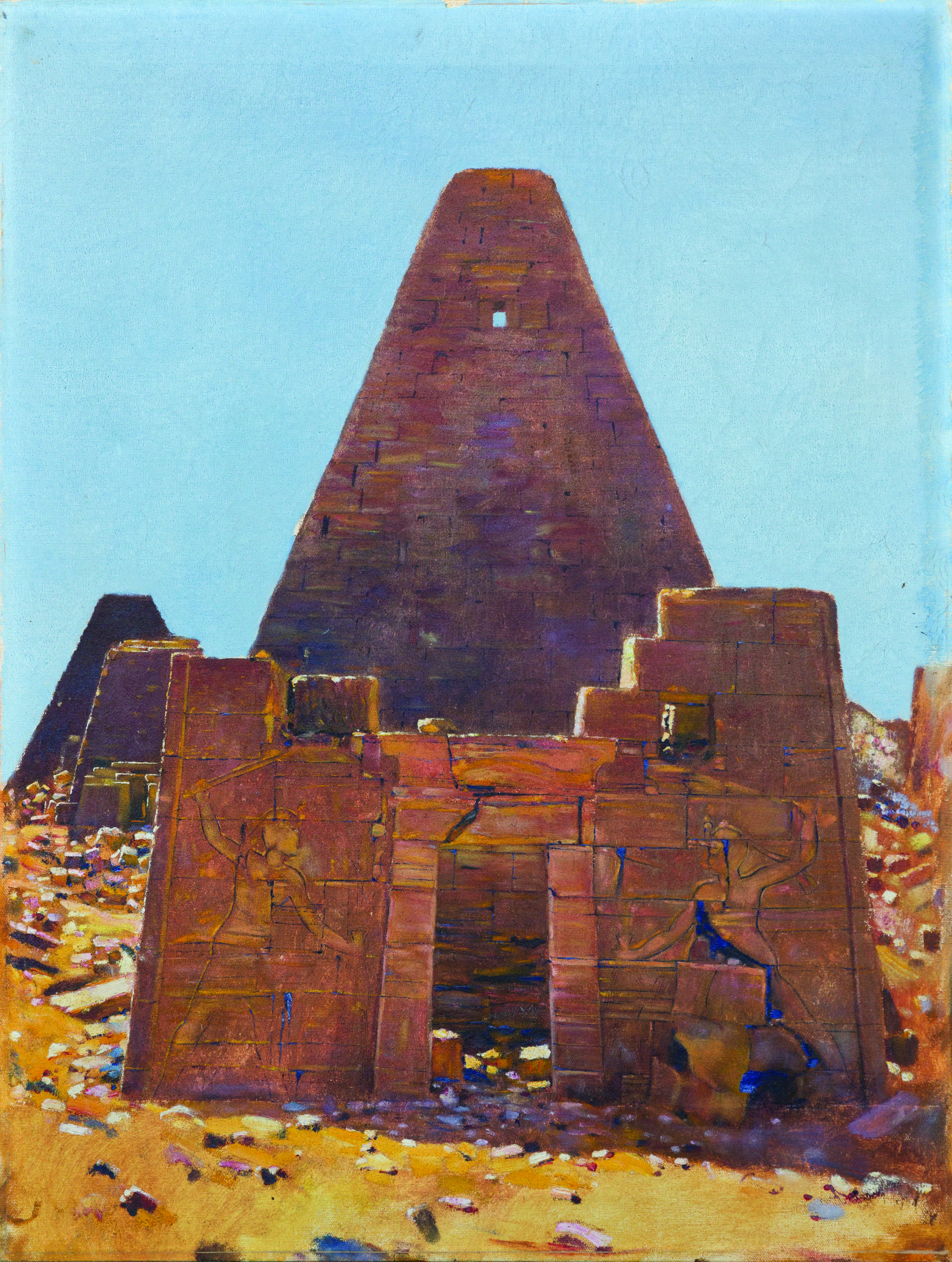

When Joseph Lindon Smith first set foot on the sands of the pharaohs, he was already a successful portrait artist from Boston. In travels to Greece and Italy, Smith had spent several years developing a technique of painting ancient architecture and relics with an astonishing sense of realism.

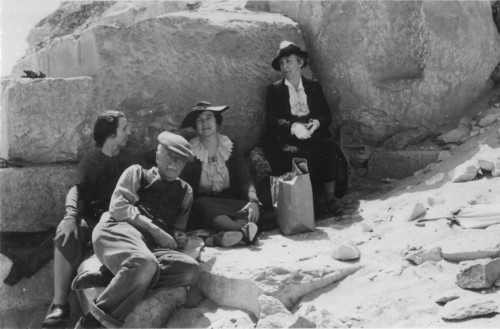

Yet this initial visit in 1898 to the land along the Nile would supply a life’s essence for the young artist. For their remaining years, Joe Smith and the charming, scholarly Corinna, his wife of more than five decades, traveled worldwide, but they returned again and again to only one hallowed place: their beloved Egypt and the monuments, tombs and art that defined their lives.

Years later, Joe Smith’s reputation in Egyptology secure, this renowned painter, educator, lecturer and dramatist would turn the enthusiasm of his eighth decade to the foundation of a new American Research Center in Egypt. He died in 1950 before he could inaugurate ARCE’s first Cairo office, but Corinna, a fluent Arabic speaker who studied the Quran, continued and expanded Joe’s influence within weeks of his death. Corinna Smith spent the rest of her years ensuring membership and funding security for ARCE.

But in December 1898, all of that was yet to come. That year, Joe opted for a last-minute trip to Cairo instead of Italy. His first morning along the Nile, Joe’s searching eyes beheld for the first time the most famous statue on earth. The spell of the Great Sphinx of Giza captured his painter’s soul, as he later described in a letter to his parents in America:

Nothing can be said or written which will give much idea of the feelings and thoughts the first sight of these stupendous things gives rise to. It is impossible to think of their makers as to realize the distance of stars or their sizes. I sat in the hot sand and looked into that battered, mutilated face…and imagined the scene if all who had ever looked at the Sphinx were seated there about me…. What an enormous living carpet would cover the land as far as the eyes of the stone god would reach.

Joe and Corinna did not realize the adventures and prominence that were to come after they were married the next year. Their united talents would forge a legacy that remains among the most fascinating of American Egyptology – a legacy allowing that living tapestry of humanity not only to experience the wondrous art of the pharaohs through Joe’s paintings, but also to benefit from ARCE’s continuing explorations of Egypt’s vital, fascinating heritage.

PAINTING AND A PUTNAM

Joseph Lindon Smith was shaped by wars. He was born during the American Civil War, and his times in Egypt were interrupted most notably by the global conflagrations of World Wars I and II. Born in 1863 in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, Smith was raised in comfortable but creative circumstances. His father was a lumber merchant, and his Quaker mother enjoyed writing and producing amateur theatricals – a trait that would stick with Smith forever. Joe’s uncle, American poet John Greenleaf Whittier, suggested to his parents that Smith be sent to Boston to listen in on lectures in architecture and other subjects at MIT. When a lecture didn’t interest Smith, he spent his time in class making sketches. One MIT professor glanced at some of those sketches and pointed Joe toward the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, where his innate artistic ability quickly distinguished him. He went on to spend two years at L’Académie Julian in Paris, returning to Boston in 1885 to open his own portrait studio.

Joe’s distinctive style, including a sense of realism and placing his subjects in outdoor light, soon attracted the attention of Harvard professor Denman Ross, who suggested Smith’s technique would benefit from more study of the masters. Ross invited Smith to travel to Europe with him, and they made several trips to paint in Athens, Rome, Florence and elsewhere. The student certainly learned from these masters, but he also repeatedly sketched and painted the historic structures and statues he saw along the way. As his reputation grew, he became friends with a network of patrons, including, in 1892 in Venice, Isabella Stewart Gardner.

Back in Boston, his business and reputation expanded and Joe began teaching decorative arts at his MFA alma mater. Channeling his mother’s theatrical instincts, he sometimes painted his subjects in period costumes. In the 1880s on a summer visit to paint a portrait commission in Dublin, New Hampshire, Joe became entranced with Dublin Lake and the surrounding art community, and his patron helped him acquire land. Joe and his lumberman father built a family summer home there at Loon Point, which later became Joe and Corinna’s permanent home for most of their lives.

Dublin, in fact, was Joe and Corinna’s starting place. At a wedding there in October 1898, just before Joe turned 35, he socialized with the delightful, intelligent Corinna Haven Putnam, daughter of George Putnam, the founder of New York’s prominent Putnam and Sons publishing company. The two stayed in touch even as Joe planned a painting trip to Italy.

SCHOLAR-PAINTER SYMBIOSIS

That Italy trip was the one diverted to Egypt – the visit that resulted in that morning moment in the sand at the Giza Plateau.

Excited by the artistic possibilities of his first sights in Egypt, Joe went to Luxor, then, fatefully, to the colossi of Ramses II at Abu Simbel. He resolved to paint as many pictures as he could. As he later remembered, he became so engrossed in his work that he was startled when an elderly woman strolled up, peered over his shoulder, studied the painting for a moment and asked: “What do you want for that picture?”

Joe later offered to sell the woman eight of his paintings and, without hesitation, she handed him a check, promising to buy others he produced. Of that encounter, Joe later recollected: “It wasn’t until later when I returned to camp that I took out the check and saw the signature.”

The name on the check was Phoebe Apperson Hearst, widow of silver magnate-turned-U.S. senator George Hearst, and the mother of William Randolph Hearst. Mrs. Hearst was also patron to archaeologist George Reisner’s famous excavations in Giza.

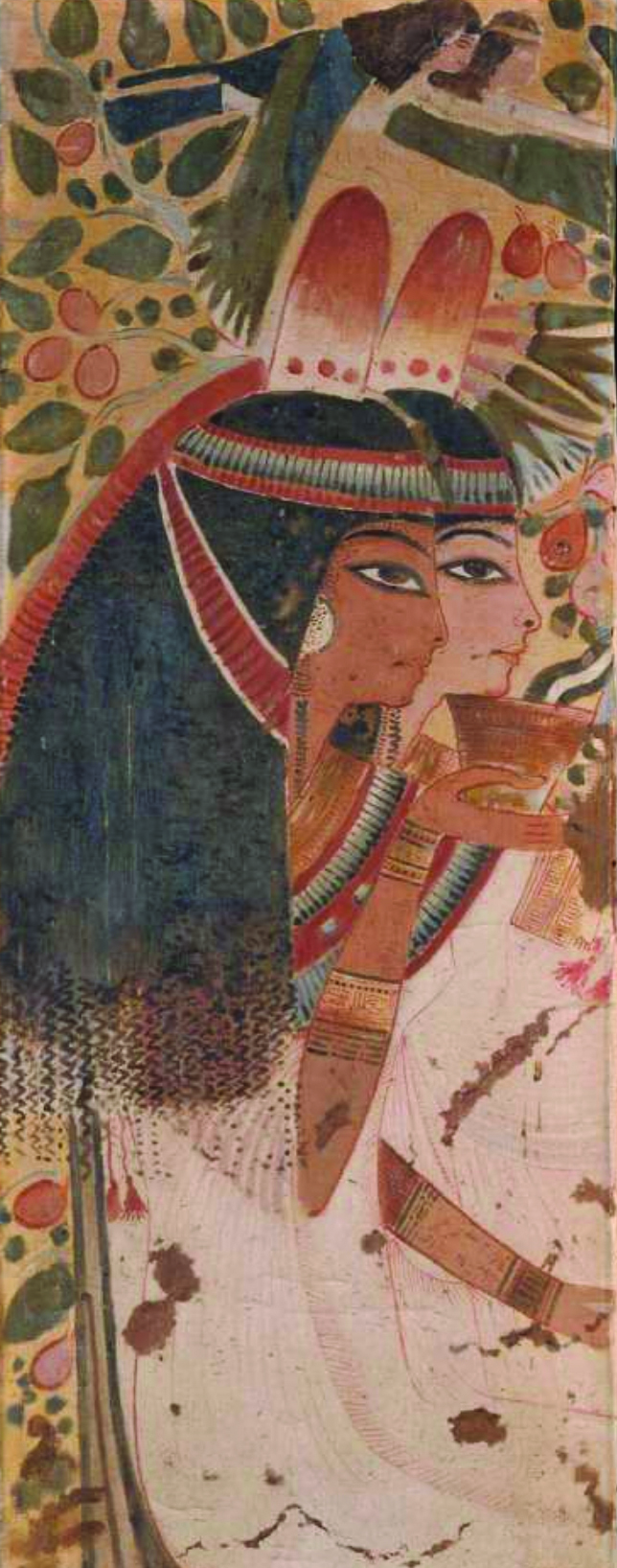

When Hearst proudly displayed Joe’s paintings to Reisner, he observed that Smith had “accomplished the impossible” by splendidly depicting three-dimensional relief carvings in a two-dimensional painting. Reisner noticed another factor that entranced him as much as it had Hearst: “Each painting was an archaeological record correct in detail, but beautiful as a picture.”

Later, Joe remembered those first moments of painting at the twin temples of Nubia as helping him realize he had found his calling: “I was not altogether happy in portraiture. My sitters were never on time, they invariably wriggled, and always had husbands or wives, mothers, and other relatives, each of whom had some criticism of the mouth, the nose, or the chin. Now Ramesses the Great is posing for me, and he is the sort of a sitter I enjoy. He will always be on time, he won’t wriggle, and his relatives, like himself, are in stone.”

When Joe returned to America, he resumed his Dublin courtship of Corinna, and they were married on September 18, 1899. You might guess the location of the honeymoon. That initial Nile trip together, one year after his first, not only solidified Joe’s decision to focus his painting on ancient subjects, but set a pattern for the couple as well – Corinna became as beguiled as Joe. In the coming months, Joe painted everywhere he could, and Corinna began her lifelong study of the Arabic language and Islam.

Joe’s paintings, plus his association with Hearst and especially Reisner, established his reputation in the growing field of Egyptology. Just two years after he met Hearst and only a year after Joe and Corinna’s marriage, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston commissioned him to paint the famous Alexander Sarcophagus that had been discovered in Lebanon. The assignment was perfect for Joe’s skills at depicting bas relief carving, but the ultimate critic was daunting: The sultan of the Ottoman Empire had just put the masterpiece sarcophagus on display at the new archaeology museum in Constantinople. Joe painted to full scale not one but three views, capturing the colorful carving with his breathtaking precision – as the sultan and everyone else noticed when the paintings were displayed next to the original at their unveiling in Turkey.

In a profile for Kmt magazine, Smith scholar Dennis O’Connor observed that the artist became a fixture at some of the most important Egyptian missions of the first half of the 20th century. “Howard Carter walked him through the tomb of Tutankhamen,” O’Connor notes. And further, “when Reisner discovered the tomb of Queen Meresankh III in 1927, Smith was on-site. He painted 14 images of the tomb’s façade and interior in less than two weeks. His painted works of the reliefs and engaged statuary within the tomb’s three subterranean chambers produce the illusion of utter three-dimensionality. The works also faithfully captured the vibrant original colors as they appeared at the time of discovery and are the only color images of the tomb in its pristine state.”

The great artist and the famous archaeologist became interlinked. The world learned of Reisner’s discoveries through the press and academic journals, but those discoveries could be seen because of Smith’s particular genius. For many years, art lovers and patrons attended annual showings presented at the foot of the Giza Pyramids where limousines lined up to see Smith’s paintings of Reisner’s latest yearly discoveries. Reisner even left Smith to monitor and oversee some excavations when he couldn’t be there himself.

Over time, as Joseph Smith biographer Dennis O’Connor found, Joe and Corinna also became known and respected in the villages near excavation sites: “Corinna had cultivated a passion for Islamic culture and customs and she was an adept speaker and writer of Arabic with all of its nuances and intricate structure. She had even earned for herself the unheard of permission to enter the male-dominated mosques to display her skill and merit by perfectly reciting, in faultless classical Arabic, hundreds of teachings from the Quran before the stunned imams who had gathered there to hear her speak.”

Corinna’s cultural, social and political savvy again and again complemented Joe’s work, eventually helping bolster America’s position in the discipline of Egyptology. Even as Corinna focused much effort toward their family, she established her own professional lecture career on Arabic and the Islamic faith. And she built her own connections before and after the 1930s, joining various women’s rights causes and working to address drug usage among Native Americans in the Western states.

30 DRUMS AND WALKING ON WATER

Joe’s paintings may have been his life’s work, but his passions extended to both casual and entrepreneurial showmanship. He enjoyed the summers at Loon Point, but also sought out other ways to relax after strenuous painting seasons abroad. He built an outdoor stage where he took to producing plays and pageants for the burgeoning art community in Dublin as popular summer diversions. As renown for his paintings grew, Joe began presenting theatricals and pageants on stages beyond those he designed and built.

Two of the most famous Smith extravaganzas took place in 1913 and 1914. The first was an Egyptian-themed masque and dinner which was held at Louis Comfort Tiffany’s showroom in New York. Later that year, he arranged an event at the Newport, Rhode Island, the estate of Arthur Curtis James called the Masque of the Blue Garden. In spring 1914, Joe staged, costumed and co-directed one of the most elaborate shows ever produced in the United States, to celebrate the 150th anniversary of the city of St. Louis. While some of his galas were less opulent, the St. Louis event featured 2,000 dancers and musicians, 30 drums and 30 cymbals, as writer Diane Larkin reported in a 2008 profile of Smith.

The shows also continued at Loon Point. Local residents joined as both performers and audience members, employing improvisational dialogue and elaborate staging. Dublin attracted many great names of the day, including Mark Twain and Amelia Earhart (Corinna’s first cousin). Joe and his parents created an artificial island, Larkin wrote, and Joe concocted a scene in which one woman appeared to walk on the waters of Dublin Lake – thanks to submerged planks. As the Smiths and their friends had children, performers became younger, and Joe began annual shows at the Dublin Lake Club. Those events continued until his death in 1950 and remain a staple of the summer program at the club today.

In all of these pageants, large and small, Joe was the creative force. But the woman in the producer’s chair often was the pragmatist of the couple. “Aunt Corinna,” as she was known in Dublin, ran the club membership of the club and shaped the pageants with her eye for detail and precision.

Among the most famous pageant tales was a performance that never happened. At the end of 1908, the Smiths were among those sleeping in the open air on the sand and rocks at archaeologist Arthur Weigall’s dig at the Valley of the Queens. One night, as they explored a nearby bluff, Joe noticed how the lamp’s shadows flickered against a natural, amphitheater-like cut in the rock. The showman immediately sensed the stage-like possibility of the stone alcove and soon announced a performance was in order. Given the contemporary view about possible curses on various tombs in Egypt, Joe steered the plot in that direction. The rehearsals began immediately, with Weigall’s wife, Hortense, to play King Akhnaten, Corinna his mother, Queen Tiy, and Joe, of course, as Horus, the incarnation of the living pharaoh. Invitations were sent, props and costumes created and the script honed.

At this point, versions of the tale differ. Joe later recounted that mysterious storms nearly blinded Corinna and Hortense with a force that put them in a Cairo hospital. Weigall never mentioned any storm and instead described the malady that struck his wife as an ectopic pregnancy. Regardless of the details, the women apparently were indeed hospitalized, and others were injured, including a broken leg for another member of the party. The story of the canceled performance evolved among the gabby friends of Weigall and the Smiths until the tale came to represent a meta-reflection of an Egyptian tomb curse. Theatrically, Smith frequently blamed the cancellation on “the curse of Amon-Ra.”

THE BRUSH OF BRILLIANCE

Joe’s famous paintings were created with a special “dry brush” technique that reduced brush marks and emphasized depth and relief. Dry brush means just that – the artist uses a dry brush without much paint instead of using water for watercolors or thinners for oils. Artists often use “dry” painting for speed and to produce a sketch-like detail with shading and shadow.

Joe also developed certain habits: His goal was to create art in replica, but that meant he would recreate the subject when it was found, not when the ancient art was created thousands of years earlier. Joe’s paintings were of archaeological discovery, so all of the stains, cracks and erosion became part of Joe’s process too. He also determined that he should paint his subjects at the same scale of the original works. Sometimes, that meant pictures twice as tall as Joe himself.

Among the first to enter and document a tomb, Joe witnessed the original pigments that were thousands of years old – and realized that those pigments would soon fade with modern exploration and its many disturbances. Joe’s paintings were not only the best record of these sites, but also moved beyond technical documentation into the realm of fine art. In short, Joe was not an epigrapher illustrating a site’s findings but an artist who wanted others to experience the glory and revelation of discovery. Numerous museums began to acquire his paintings and, for some visitors, they served as a substitute for a visit to Egypt.

Joe joked that his paintings were “better” than the originals because his didn’t fade with time, and because they could be viewed miles or continents away. More seriously, he often said in his later years that he had spent a lifetime learning how to paint: “I regard my art as an interpreter of the past, rather than a mirror.”

Back in America, Joe traveled and displayed his paintings, delivering lectures on the growing field of Egyptology. Many in the audience would never be able to afford or accommodate Joe’s grandiose pictures. But they clamored for smaller copies. Diana Larkin pointed out in her 2008 online profile that such paintings were both valuable and popular. Of course, this was an era when photography was only black and white for the most part, so Smith’s realistic, careful paintings were the best way to view an ancient tomb without actually visiting it.

At times, Joe demonstrated his techniques during a lecture. Larkin described how he once showed a lecture audience a portrait he had painted of an Italian boy. “Then he transformed it,” Larkin wrote. “He changed the skin tone and brightened the sky, turning his work into a portrait in the manner of Titian. Next, he simplified the planes and toned down the color contrast, until he had a totally different style, suitable for a mural.” Joe was a painter, but always a teacher.

Throughout their years in Egypt, Joe and Corinna’s respect for the culture earned high regard in both village squares and Cairo offices. His paintings provided a way for the outside world to see the glory of Egypt and for the Egyptian population to appreciate its own history and culture. Joe became the only American to have his art displayed in the galleries of the Egyptian Museum – an honor repeated several times – and he later began teaching his technique to Egyptian students at the behest of the Ministry of Education. The honors continued in April 1949, when Mahdi Allam, dean of Arabic inspectors for the Ministry of Education, wrote a pamphlet about his new friend.

Allam’s study tells the story of Joe, already in his 80s, at a dinner in Cairo. When the host remarked on how little food he placed on his plate, Smith replied: “I have to be careful now that the season is starting. I mustn’t allow myself to grow fat, as I have sometimes to squeeze myself into narrow places inside tombs and other ancient buildings in order to paint my pictures.”

Amid the attention and shows and teaching, amid the fame and respect, Joe Smith kept painting. And as much as possible, from the earliest years to the last, he wanted Corinna at his side. The joke between them was that Joe believed he worked even faster when she was nearby, with her explaining that the increased speed “was out of fear.”

Corinna, as practical and charming as ever, was never eclipsed by her partner. O’Connor writes: “She possessed and maintained personal contacts within government circles and she was well-known and respected in the society worlds of many prominent government men in Washington. In her youth, she’d been introduced to politics because she was the daughter of George Putnam, the influential New York publisher who maintained many government contacts and affiliations. Before and after her marriage, she’d often acted as her father’s “hostess” and she became well recognized not only for her beauty and charm, but also for her acuity and intelligence with regard to political issues of the day.”

JOE, CORINNA AND A NEW PASSION

What would become the American Research Center in Egypt was first envisioned in a 1948 magazine article by Sterling Dow, then president of the Archaeological Institute of America. Dow and others organized a meeting that year in Boston, and the planning began. The Smiths could not attend that first meeting, but Dow and the others were aware of their interest, the value of their fame and especially the couple’s support for the center’s goal to promote independent and collaborative research in Egypt.

By April 1950, at age 86, Joe was functioning as president pro tem of the ARCE executive committee in Cairo, arranging a meeting at the American Embassy. The minutes show Joe urged the group to work with Egyptians as much as possible while also recruiting scholars from top U.S. universities. “I believe that fine things of the past will continue to attract the fine people of the present,” he pronounced.

Joe was chosen for the ARCE board and Corinna was elected to honorary membership. He promptly proposed that the name of an Egyptian liaison officer for American scholars be inscribed along with American names on the foundation stones of the new center in Cairo. In his biography of Smith, O’Connor writes: “Once again, Smith was the consummate public relations bridge between the two countries. In Egypt he unfailingly promoted publicly the interest and concern of America, and once back in America, he made the conspicuous point of singling out and commending Egyptian nationals on a par with their American counterparts.”

Smith’s stress on bridge building between the U.S. and Egypt was a key part of ARCE’s organizational principles, which he and others pushed to declare that ARCE “shall seek cooperation with those American, foreign or international governmental agencies which deal with international cultural relations but shall have no organic affiliation with any agency of the United States government or of any other government.”

But the grand plans and leadership role Smith envisioned would not happen. On October 18, 1950, just after turning 87, Joe died in his sleep. He would have assumed the directorship of the Cairo office the next month. The light of his art continues in hundreds of paintings displayed worldwide, but he would create no more. The memories of Joseph Lindon Smith were left to the history he so carefully recorded.

Fortunately, someone else was waiting to assume his role – someone whose organizational expertise might carry her influence beyond Joe’s prominence. At the November 21, 1950, ARCE board meeting, less than a month after Joe’s death, his widow was appointed to the board of governors. Over the next 15 years, O’Connor writes, Corinna actively continued her commitment and service to the organization, especially in membership and funding. At the ARCE Annual Meeting the following year, Corinna reported a sizable bequest made by her New York friend Mrs. Godfrey Peckitt in memory of Joe Smith and George Reisner. The minutes of that meeting also noted that “a significant increase in membership can be attributed to the untiring efforts made by Mrs. Joseph Lindon Smith. Ninety-four new memberships have been recorded and sixty-six of those have already been paid up. ARCE’s bank balance has tripled from the year before.”

By 1953, the minutes for ARCE’s Annual Meeting praised Corinna for promoting a new membership committee, with another notation thanking her for helping bring the center’s bank balance to its highest level ever. As O’Connor writes: “This happy turn of events was assuredly the result of her committed efforts to the organization, coupled with her wide field of benefactors and Washington elite. In January 1954 Corinna was appointed by unanimous vote of the trustees to a year’s tenure on the executive committee.”

Meanwhile, she and others worked to keep the young organization neutral amid the political and economic turmoil in Egypt. By 1958, with Corinna now in her 80s, the board voted “to make her an honorary member of the executive committee in the hope that she would meet whenever possible and would continue to aid the center as she had so greatly in the past with her invaluable suggestions and advice.”

The assets of ARCE had grown to exceed $30,000 – a sum that seems paltry now but was healthy for that era. Corinna continued to work behind the scenes for ARCE and eventually published her own autobiography, Interesting People: Eighty Years with the Great and Near Great. The organization shows up on one of the book’s final pages, in a chapter the always charming author called “How to be Useful Over Eighty!”

By 1964, Corinna was back on the ARCE board. Her final executive meeting was in November 1964, when she resumed her persistent advice urging “all members of the board to make an effort to secure additional members.” She also reported that “there was a great deal of interest in the center to be found in Dublin, New Hampshire” and that it was her “plan to secure for 1965, members of that community to become active members of ARCE.” At age 90, Corinna Putnam Lindon Smith died on a June day in Dublin, the beloved home to the family and life she and Joe built there.

After 16 years of support and work, ARCE faced a promising future. As Dennis O’Connor concludes in his chapter on the Smiths and ARCE: “It is never to be forgotten again that it was through the Smiths’ foresight, planning and effort, and most certainly as a result of their international and very public positions over the course of their lives, that they left behind them a functioning and dedicated entity that would fulfill their greatest ambitions and hopes for its success.”

Acknowledgements

Scribe magazine gratefully acknowledges research and writing for this article by ARCE member and Chicago chapter President Dennis O’Connor, which includes work from his published article in Kmt and a future book about Joseph Lindon Smith that will detail Smith’s life and career as well as his seminal role in the creation of ARCE; from an online profile of Joseph Smith by Diana Wolfe Larkin, published in 2008 by the Monadnock Art Friends of the Dublin Art Colony; and from a brief biography published in 1949 in Arabic and English in Cairo by Dr. Mahdi Allam, then dean of Arabic inspectors for the Ministry of Education.